CINEINFINITO / Cine Club Filmoteca de Cantabria

21 de Octubre del 2017, 17:00h Filmoteca de Cantabria

Calle Bonifaz, 6

39003 Santander

Programa:

Bertha’s Children (1976) 16mm / b&w / 7 min

Future Perfect (1978) 16mm / color / 11 min

Murray & Max Talk About Money* (1979) 16mm / color / 13 min

Terms of Analysis** (1982) 16mm / color / 16 min

(ratio de proyección *1.78: 1 y **1.66:1, a decisión de los autores)

Formato de proyección: 2K / HD (Nuevos transfers digitales supervisados por Grahame Weinbren y Roberta Friedman para esta sesión)

(Agradecimiento especial a Roberta Friedman y Grahame Weinbren)

Roberta Friedman es una cineasta y productora que tiene en su haber un gran número de películas y vídeos que han sido exhibidos en muchos lugares de Estados Unidos y Europa. Sus proyectos alternan desde obras artísticas experimentales hasta películas narrativas, y documentales y series de televisión. Es miembro fundador del fondo iota, que financia obras de animación abstracta y en los últimos tiempos ha producido una serie de instalaciones de vídeo llamada Cosmópolis: 49 valses para el mundo, sobre los sonidos que desaparecen en las ciudades más expuestas al cambio, incluyendo Nueva York, Pekin, El Cairo y Detroit. Ella empezó su carrera en la radio, y ha tenido un programa de larga permanencia en la emisora KPFK de Los Angeles.

Friedman tiene un master en cine del Instituto de las Artes de California y actualmente es profesora asociada y coordinadora de programación de cine en la Escuela de Comunicaciones y Periodismo de la Universidad del Estado de Montclair en New Jersey.

Grahame Weinbren es cineasta, escritor y editor. Su práctica artística incluye instalaciones interactivas, cine artístico y documentales experimentales. Sus escritos sobre cine, medios de comunicación, arte y cuestiones filosóficas asociadas a las nuevas tecnologías han tenido amplia difusión. Es editor senior del Millennium Film Journal y profesor de la Escuela de Artes Visuales de Nueva York. Estudió filosofía en la University College London y en la Universidad SUNY de Buffalo.

Cuando trabajaban juntos en el Instituto de las Artes de California en los años 70, Friedman y Weinbren exploraron con singular ingenio en sus primeras películas las estructuras matemáticas, el cine como música, la sintaxis de las películas y las narrativas de vanguardia, antes de orientarse a las instalaciones de vídeo multimedia e interactivas, de las cuales El rey de los alisos (1983-86, Whitney Biennial 1987) fue un ejemplo que rompió moldes. Ambos han seguido colaborando en paralelo a su obra individual.

[Roberta Friedman is a filmmaker and producer with work that spans a large assortment of film and video productions shown widely in the United States and Europe. Projects have ranged from artistic, experimental works to narrative features, television documentaries and series. She is a founding board member of the iota fund that supports abstract animation, and most recently has been producing a series of video installations called Cosmopolis: 49 Waltzes for the World about the disappearing sounds in cities on the cusp of change including New York, Beijing, Cairo, and Detroit. She began her media career in radio and had a long running show on KPFK in Los Angeles.

Friedman has an MFA in Film from California Institute of the Arts, and is currently an associate professor and coordinator of the Film Program in the School of Communication & Media at Montclair State University in New Jersey.

Grahame Weinbren is a filmmaker, writer and editor. His art practice includes interactive installations, artists’ cinema, and experimental documentaries. His writings about cinema, media art, and philosophical issues generated by emerging technologies are widely published. He is the senior editor of the Millennium Film Journal and a member of the graduate faculty of the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He studied Philosophy at University College London and SUNY Buffalo.

Working together at CalArts in the 1970s, Friedman and Weinbren explored mathematical structures, film as music, movie syntax and avant-garde narratives with a singular wit in their early films before turning to multimedia and interactive video installation, of which The Erl King (1983–86, Whitney Biennial 1987) was a groundbreaking example. They have continued to collaborate while also working individually.]

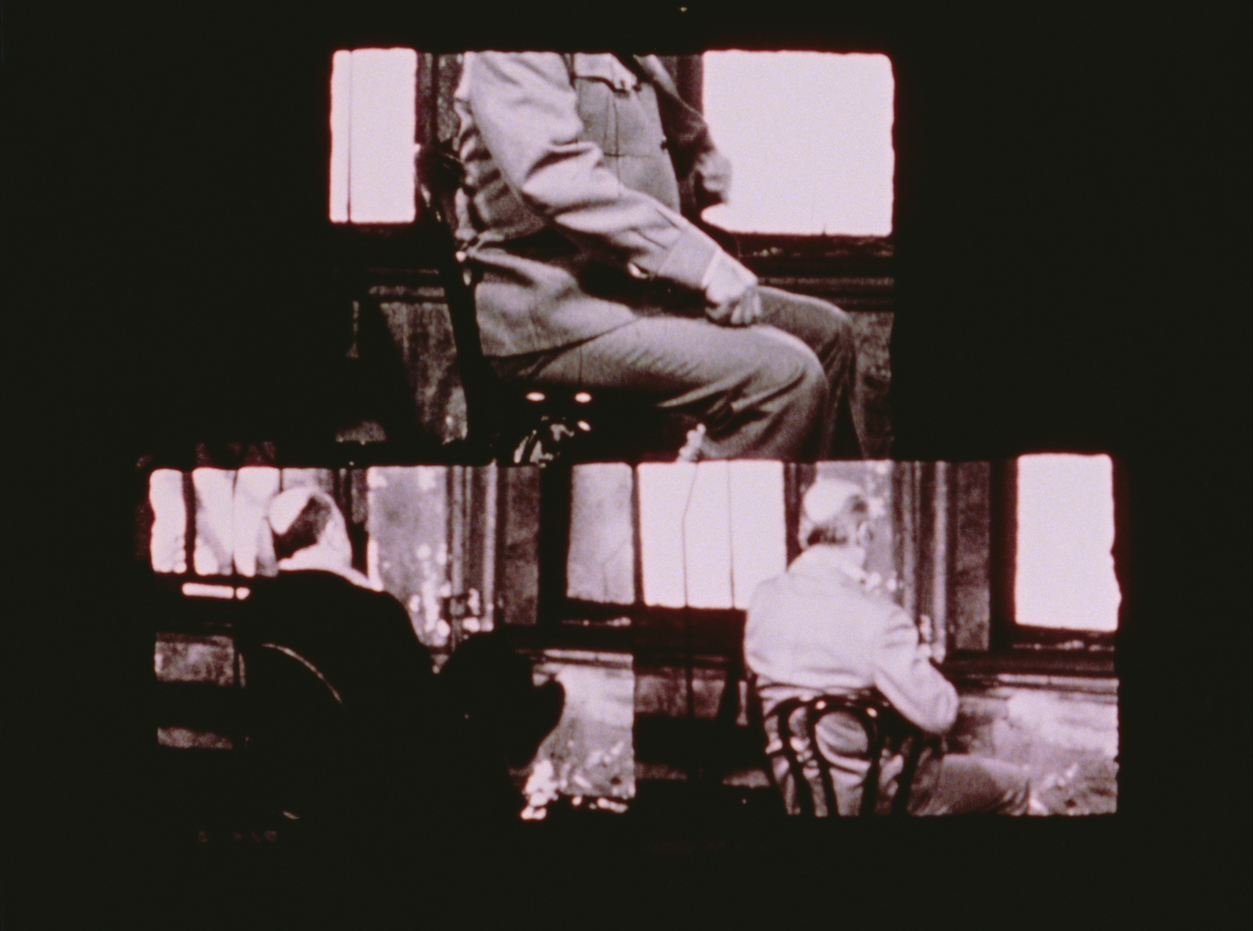

Bertha’s Children (1976)

Mi tía abuela Bertha tuvo siete hijos, que tienen ahora entre cincuenta y sesenta y cinco años. Todos crecieron en la ciudad de Nueva York e incluso después de llegar a adultos y tener sus propias familias siguieron viviendo en la misma zona. Cuando fui a Nueva York un invierno le pedí a cada uno de ellos que apareciera en una película, y todos aceptaron. Cuando volví el invierno siguiente, sin embargo, solo David, Marty, Aaron, Bernie y Thelma quisieron hacerlo. Frieda, preocupada por los lunáticos que pudieran ver la película y luego escribirle asquerosas cartas anónimas, se negó, y Sylvia estaba aquella vez en Florida. —Roberta Friedman

La intención era construir una película a partir de una serie de contrastes y similitudes: entre cinco hermanos, entre estos cinco y su entorno, entre el movimiento “real” y el “fílmico”, y entre la presentación de información verbal y visual. Uno de nuestros experimentos al hacer películas es introducir en la composición un cierto número de indeterminaciones, de modo que algunos aspectos de la obra resultante son deliberadamente impredecibles. En este caso, la imagen estaba compuesta según un esquema estricto en dos rollos separados, y la banda de sonido en cinco. La combinación de estos elementos se podía ver y oír por primera vez al proyectar el copión en el laboratorio. –Grahame Weinbren

El artista no puede imaginar su arte, y no puede percibirlo hasta que está completo. –Sol Lewitt

Cuatro personas emparentadas actúan y describen sus actividades de todos los días. Fotografiados por separado, aparecen en las sub-pantallas en que se divide la película en grupos de uno a cuatro. El centro del experimento es el tiempo: las acciones y los comentarios se interrumpen al azar. El flujo temporal es Avance: corte, Avance: corte. En el corte, la figura parece dar un salto hacia atrás, a un estado previo de la secuencia. La distribución espacial de la pantalla se recompone con frecuencia, como para permitir que las figuras, solas en sus pantallas, bailen juntas en la imaginación. Las sub-pantallas tocan los bordes y su fricción tiene algo de la aspereza de las paredes de una vieja habitación. Gruesas y redondeadas caderas golpean contra estilizadas sillas de madera, caras redondas sonríen y hablan, suaves dedos titubean sobre chaquetas planchadas con esmero. Gertrude tenía razón… –Pat O’Neill

[My great aunt Bertha had seven children who are now between fifty and sixty-five years old. They all grew up in New York CIty and, even after they became adults and had their own families, lived in the same geographic region. When I visited New York one winter, I asked each of them to be in a film, and all of them agreed. When I returned the following winter, however, only David, Marty, Aaron, Bernie and Thelma would do it. Frieda, concerned about the crazy people who might see the film and then write her nasty anonymous letters, refused, and Sylvia was in Florida at the time. –Roberta Friedman

The intention was to construct a film out of a set of contrasts and similarities: between five siblings, between these five and the environment in which they are placed, between ‘real’ and ‘filmic’ motion, and between the verbal and visual presentation of information. One of our practices in creating film is to build into the composition at least one set of indeterminacies, so that some aspects of the resultant work are deliberately unpredictable. In this case, the image was composed according to a strict scheme on two separate rolls, and the sound track on five. The combination of these eight elements was seen and heard for the first time when the answer print was screened at the lab. –Grahame Weinbren

The artist cannot imagine his art, and cannot perceive it until it is complete’ –Sol Lewitt

Four related persons perform and describe four everyday acts. Photographed separately, they occur in the film in sub-screens in groups from one to four. The center of the experience is time: actions and commentary are interrupted randomly. The flow of time is Forward: cut, Forward: cut. In the cut, the figure seems to jump back to an earlier stage of the motion. Spatial arrangement of the screen is frequently re-arranged so as to allow the figures, alone in their screens, to dance together in the illusion. The sub-screens touch at the edges, and their friction has some of the grittiness of the walls of the old room. Thick round buttocks pound against spindly wooden chairs, round faces smile and enunciate, smooth fingers fumble neatly pressed jackets. Gertrude was right…. –Pat O’Neill]

Future Perfect (1978)

Para concluir, describiré una película que hice con Roberta Friedman en 1978 que se llama Future Perfect. La rodamos y terminamos en el altillo ilegal en que vivíamos en aquella época, encima de un bar irlandés en la esquina de Wall Street y Water Street en Nueva York, a un par de bloques de donde late el pulso financiero del capitalismo occidental. La habitación trasera del altillo era oscura y estaba sin terminar, y su única ventana daba a otro edificio que cortaba el paso a la luz del día. Teníamos allí nuestros focos, nuestras herramientas, nuestras bobinadoras y nuestro visor, así como una moviola de 16 mm, y cuando nos visitaban los amigos podían dormir en una cama supletoria en aquel estudio sombrío.

Un amigo nuestro era estudiante de arquitectura y le pedimos que nos dibujara una vista en planta del estudio, que tenía más o menos la proporción de una pantalla de cine de formato ancho. Pensamos en las formas en que se podían trazar marcas geométricas sobre esta pantalla –un rectángulo en torno a los bordes, una diagonal de una esquina a otra y vuelta, marcas de puntos bajo uno de los bordes, una línea que cortara el borde inferior y volviera a emerger en el de arriba como si atravesara la horizontal del marco, arcos en los cuadrantes superior e inferior. Planeamos movernos a lo largo de estos diseños, y grabar nuestro recorrido en película de 16 mm. El fotógrafo Anthony Forma accedió a ayudarnos. Nos dimos cuenta de que la experiencia primaria del cine fotográfico es indéxica –el espectador mira a través de la pantalla, como una ventana espacio-temporal, el momento y lugar en que la imagen fue hecha. Sin embargo, contra este aspecto representativo de lo cinematográfico queríamos desplegar el hecho de que la imagen fílmica es materialmente una pequeña superficie plana transparente, cuya función es transformar la luz que pasa a través de ella. Queríamos hacer una película que subrayara los aspectos materialistas e ilusionistas del cine, con los dos aspectos flotando en paralelo. También nos interesaba en aquella época el hecho de que el trabajo que lleva hacer una película no está inscrito en la obra terminada; más bien, en la mayor parte de los casos, se oscurece deliberadamente, y nosotros queríamos que el trabajo implícito en la construcción de la película formara parte de su contenido. La idea general, en otras palabras, era exponer algo. Así que, después de trazar los recorridos de nuestra cámara a través de la habitación, formando estas figuras geométricas, situamos señales troqueladas en los puntos finales de los movimientos de cámara. Estas señales indicaban nuestras intenciones para terminar la película. Detendríamos la cámara delante de cada una de estas señales. El plan era dibujar en la película expuesta y revelada las mismas formas geométricas que habíamos trazado con los movimientos de cámara para crear las imágenes fotográficas. Solo después de haber dibujado estas figuras directamente en la superficie de la emulsión, la película estaría terminada. Utilizamos una calculadora para obtener varias series numéricas decrecientes, que determinarían los intervalos entre las marcas que haríamos en la película. Las señales troqueladas eran, por ejemplo:

UN RECTÁNGULO HABRÁ SIDO DIBUJADO A TRAVÉS DE ALGUNOS FOTOGRAMAS. EL NÚMERO DE FOTOGRAMAS ENTRE LOS DIBUJOS SE REDUCE SEGÚN UNA SERIE DE FIBONACCI

En otras palabras, los textos fotografiados en la película enuncian la fórmula que genera las imágenes que de hecho dominan la película. El plan de rodaje presenta los textos troquelados con una función doble de hito cuentakilómetros y poste indicador: como metas a las que apuntan los erráticos movimientos de cámara de modo que la cámara se detiene cuando los encuentra, y también como descripciones de la composición visual de la película terminada, y además como instrucciones que los cineastas deben seguir. Es obvia la conexión con un artista conceptual como Sol Lewitt, cuya obra de aquella época consistía en instrucciones para realizar una pintura o un dibujo.

Las series matemáticas fueron calculadas de manera que cada una proporcionara valores de menos de un fotograma (como si fuera una serie asintótica) o terminara al cabo de ocho minutos después del inicio. De esta forma, Future Perfect construye una progresión de densidad y ritmo que sigue principios matemáticos, hasta que hacia los ocho minutos aparece una nutrida exposición de figuras dibujadas y emerge una música (puesto que cada dibujo tenía que ser acompañado por un sonido producido con un arco sobre un utensilio de cocina) que se transmuta en un zumbido metálico continuo y discordante en cuanto el espacio entre los dibujos y los sonidos se vuelve inferior a un fotograma, y en efecto continuo. Futuro perfecto era lo que pensábamos sobre la terminación de la película, y también, desde luego, el tiempo gramatical en que estaban troqueladas las frases sobre intenciones en las paredes del estudio. Imprimimos listas de los números de fotogramas en los que íbamos a hacer marcas, pusimos la película diapositiva expuesta y revelada en una mesa de rebobinado del estudio, y empezamos a rotular esos fotogramas con tinta transparente especial para diapositivas y transparencias retroproyectadas. En contraste con el rodaje, que duró unos agónicos pero delimitados 33 minutos (con la Arriflex de 16 mm a ocho fotogramas por segundo), el rotulado de los fotogramas nos llevó meses, pero mantuvimos en mente el futuro perfecto, el tiempo diferido en que la película estaría rotulada en su totalidad y completa.

Los espectadores son devueltos al tiempo por el tiempo gramatical de los textos, mirando hacia adelante a lo largo de la película desde el tiempo de la producción al tiempo en que se habrán completado las marcas, que es, por supuesto, el tiempo del presente continuo en que la película está terminada y se exhibe al fin. Así que la película invita a sus espectadores a ver su trayecto a través y alrededor de múltiples temporalidades, y también es un registro nostálgico del oscuro altillo del distrito financiero en el que vivíamos cuando éramos unos jóvenes cineastas, y un registro de las diferentes clases de trabajo que supone hacer una película, con la ayuda de equipos mecánicos, materiales y productos químicos sensibles a la luz, en contraste con el arte más tradicional del rotulado, y de la forma en que se despliegan uno contra otro los dos tipos de trabajo en paralelo con la inexorable relación entre la tecnología y las leyes naturales, y todo esto más o menos en un simple gesto desenrollado en una tira de tiempo de once minutos, que hace todo lo posible para evadirse más allá de su propio marco temporal mediante referencias claras a su propio futuro y su propio pasado. –Grahame Weinbren. Experimental Film and Video, editado por Jackie Hatfield.

“Un film que, siempre inacabado, mira hacia adelante a un futuro en el que él (y todo lo demás) será perfecto”. –Roberta Friedman & Grahame Weinbren. Catálogo de Film- makers’ Cooperative

FUTURE PERFECT es una película casi algorítmica, basada en un grupo de series matemáticas decrecientes que produce ritmos visuales y auditivos más allá del control de los cineastas. –International Film Festival Rotterdam, 2011

[I’ll conclude by describing a film I made with Roberta Friedman in 1978 called Future Perfect. It was filmed and finished in the illegal loft we were living in at the time, above an Irish bar on the corner of Wall Street and Water Street in New York City, a couple of blocks from the financial heartbeat of Western Capitalism. The back room of the loft was dark and unfinished, its one window looking out onto another building that cut out any daylight. We had our lights, our tools, our rewinds and viewer set up there, as well as a 16mm Moviola, and when friends visited they would sleep on a trundle bed in that gloomy studio.

A friend of ours was an architecture student and we asked him to draw a plan view of the studio, which was more or less in the ratio of a wide-screen cinema frame. We thought about the possible ways geometric marks could be made on this film frame — a rectangle around the edges, a diagonal line from one corner to the other and back, dots down one edge, a line that would cut the bottom edge and re-emerge at the top edge if it traversed the horizontal frame line, arcs in upper and lower quadrants. We planned to move in these patterns through the room and record our the path on 16mm film. The cinematographer Anthony Forma agreed to help us. We recognized that a primary experience of the photographic cinema is indexical—the viewer looks through the frame like a time-space window into the period and place when the image was produced. However, against this depictive aspect of the cinematic we wanted to play the fact that the film image is materially a small flat transparent surface the function of which is to transform the light that passes through it. We wanted to make a film that highlighted the materialistic and illusionistic aspects of cinema while keeping both of the aspects floating in parallel. We were also interested at the time in the fact that the labor that it takes to make a film is not inscribed in the finished work; rather in most cases it is deliberately obscured, and we wanted the labor involved in the construction of the film to be part of its content. The general idea, in other words, was to expose everything. So we after we plotted our camera paths through the room, forming these geometric figures, we placed stenciled signs at the end points of intended camera moves. These signs indicated our intentions for finishing the film. We would stop the camera in front of each of the signs. The plan was to draw on the exposed and developed film the same geometric shapes that we had plotted with the camera movements to create the photographic images. Only after these figures had been drawn directly on the surface of the emulsion would the film be finished. We used a calculator to figure out a series of decreasing numerical series, which would determine the intervals between the marks that we would place on the film. Thus the stenciled signs were, for example:

A RECTANGLE WILL HAVE BEEN DRAWN AROUND SOME FRAMES. THE NUMBER OF FRAMES BETWEEN DRAWINGS DECREASES ACCORDING TO A FIBONACCI SERIES

The photographed texts in the film, in other words, state the formulae that generate the images which eventually dominate the film. The shooting plan features the stenciled texts which function both as milestones and signposts, as targets aimed for in the erratic camera movements so that the camera pauses when it finds them, as descriptions of visual composition of the final film, as well as plans for the filmmakers to follow. The connection is obvious with a conceptual artist like Sol Lewitt, whose work at that time consisted of plans as to how a painting or drawing was to be realized.

The mathematical series were calculated so that each one would yield values of less than one frame (if it was an asymptotic series) or would end, at about eight minutes from the beginning. Thus Future Perfect gradually builds in density and rhythm according to mathematical principles, until at about eight minutes there is a copious display of drawn figures and an emergent music (since each drawing was to be accompanied by a sound produced by bowing a kitchen utensil) which transmutes into a continuous discordant metallic humming as the space between drawings and sounds becomes less than a single frame and in effect continuous. Future Perfect was both how we thought of the completion of the film, plus of course the grammatical tense in which the sentences about intentions were stenciled on the walls of the studio. We printed out lists of the frames numbers that were to receive marks, set the exposed and developed reversal film on a rewind bench in the studio, and began to mark the appropriate film frames with special transparent inks intended for overhead transparencies and slides. In contrast to the shooting, which lasted an agonizing but delimited 33 minutes (running the 16mm Arriflex at eight frames per second), the marking of the frames took months, but we kept the perfect future in mind, the deferred time when the film would have been fully marked up and complete.

Viewers are thrown back in time by the tense of the texts, looking forward through the film from the time of production to the time when the various marks will have been made, which is of course the time of the continuous present when the film is finished and finally shown. So the film invites its viewers to see their way through and around multiple temporalities, while it is also a nostalgic record of the dark loft in the financial district where we lived as young filmmakers, and a record of the different kinds of work it takes to make a film, with the aid of mechanical equipment, light sensitive materials and chemistry, in contrast to the more traditional way of making art by marking materials, and the way the two types of labor play against each other parallel to the inexorable relationship of technology to natural law, and all of this is realized in more or less a single gesture unwound into an eleven minute strand of time, which does its best to break out beyond its own temporal frame by referring clearly to its own future and its own past. –Grahame Weinbren. “Experimental Film and Video” edited by Jackie Hatfield.

“A film which, always unfinished, looks forward to a future when it (and everything else) will be perfect.” –Roberta Friedman & Grahame Weinbren, Film-makers’ Cooperative catalog

FUTURE PERFECT is an early algorithmic film, based on a collection of decreasing mathematical series that produce visual and auditory rhythms beyond the control of the filmmakers. –International Film Festival Rotterdam, 2011]

Murray & Max Talk About Money (1979)

Siempre estamos interesados en construir formas de evocación de los placeres del cine sin aceptar implícitamente una ideología –de pasividad, manipulación y violencia reprimida– que rechazaríamos explícitamente. ¿Puede haber películas que sigan siendo cinematográficas sin caer en una u otra forma de pornografía? Murray and Max… es, en parte, una propuesta, un anteproyecto, para una forma de cine así. –Roberta Friedman y Grahame Weinbren. Recuperando la vanguardia de Los Angeles: Las cosas siempre se tuercen. Notas de programa, 2009.

[“We are always interested in constructing ways of evoking the pleasures of cinema without implicitly accepting an ideology–of passivity, manipulation, and repressed violence–that we would explicitly reject. Can there be films that remain cinematic without indulging in one form of pornography or another? Murray and Max… is, in part, a proposal, a blueprint, for such a form of cinema.” –Roberta Friedman and Grahame Weinbren –Restoring the Los Angeles Avant-Garde: Things Are Always Going Wrong Program Notes, 2009.]

Terms of Analysis (1982)

Hecha en colaboración con el compositor y trombonista James Fulkerson, que aparece a lo largo de la película. Aunque no nos dimos cuenta entonces, esta fue nuestra última película en 16 mm. Mirando de reojo a algunos de los términos que se usaban en la época en el análisis de películas y medios de comunicación (muchos de los cuales todavía siguen vivos en la jerga académica), se enfrenta a eventos personales que cambian la vida y a la documentación del cambio –de las estaciones, de los espacios de vida y trabajo, y de dos ciudades. –Roberta Friedman y Grahame Weinbren.

Made in collaboration with composer/trombonist James Fulkerson, who appears throughout the film. Though we didn’t know it at the time, this was our last 16mm film. Looking askance at some of the terms used in film and media analysis of the time (many of them still alive in academic jargon), is set against personal, life-transforming events and documentation of change — of seasons, of living and working spaces, and of two cities. –Roberta Friedman y Grahame Weinbren.

(Traducción: Javier Oliva)