CINEINFINITO / Centro Cultural Doctor Madrazo

Lunes 31 de Octubre de 2022, 18:30h. Centro Cultural Doctor Madrazo

Calle Casimiro Sainz, s/n

39004 Santander

Programa:

– Le retour à la raison (1923), 16mm, b&n, silente, 3 min

– Ballet Mécanique (1924), 16mm, b&n, silente, 12 min (como camarógrafo)

– Anemic Cinema (1926), 16mm, b&n, silente, 7 min (como camarógrafo)

– Emak-Bakia (1927), 16mm, b&n, silente,16 min

– L’étoile de Mer (1928), 16mm, b&n, silente, 16 min

– Les mystères du château de Dé (1929), 16mm, b&n, silente, 20 min

Formato de proyección: HD (copias restauradas)

(Agradecimiento especial a Man Ray Trust / ADAGP)

Man Ray, seudónimo de Emmanuel Radnitzky (Filadelfia, 27 de agosto de 1890 – París, 18 de noviembre de 1976) fue un artista modernista estadounidense que pasó la mayor parte de su carrera en París (Francia). Fue un importante contribuyente a los movimientos dadaísta y surrealista, a pesar de que sus vínculos con cada uno eran informales. Él era conocido en el mundo artístico por su fotografía avant-garde, y también fue un reconocido fotógrafo de retratos.

Man Ray escribió que “Todas las películas que he hecho fueron improvisaciones. No escribí guiones. Era cine automático.” Sin embargo, el automatismo del rodaje adquiría su forma final mediante el montaje. Al preparar Emak Bakia recuerda que “cuando sintiera que tenía material suficiente para una película corta, montaría las secuencias en una cierta progresión, consideraría acabado el trabajo”. En el rodaje Man Ray se centró en determinados motivos, movimientos y efectos que fueron combinados mediante el montaje para articular varios episodios o secuencias cuyo ensamblaje dio lugar a la película surrealista.

(…) En Emak Bakia podemos ver la primera y más completa afirmación cinematográfica de Man Ray. Su primer experimento con el cine, Le Retour à la Raison, era aún poco personal. Su siguiente película, L’Etoile de Mer, aunque es una interpretación libre de un poema de Desnos, no deja de ser la adaptación de una obra ajena (y, en concreto, de un poema surrealista). Le Mystère du Chateau du Dés, su última obra terminada anterior a los años 40 está otra vez muy vinculada al encargo que la originó (una película de una fiesta en el castillo del vizconde de Noailles). Hay que reconocer a Man Ray el valor artístico de estas otras películas, pero en ninguna de ellas alcanzó la viveza, versatilidad y la pura poesía visual de Emak Bakia. Esta obra permanece en la encrucijada de Dada y el surrealismo. Sobre un flujo de abstracción subterráneo, la película reúne a ambos movimientos en armonía.

(…) La comparación de dos objetos funcionalmente distintos pero similares en apariencia, ojos y focos, ofrece una nueva forma de percibirlos en términos recíprocos. También, en un cierto sentido, las formas luminosas rotatorias crean una nueva realidad visual para el espectador. Podemos encontrar en la película motivos e imágenes específicamente surrealistas, como el ojo inquietante y la mujer misteriosa. Aparece también el proceso del despertar, un tema fundamental de los surrealistas, que trataban de abolir la barrera entre el sueño y la vigilia. Y en un sentido más amplio, toda la película es producto de una imaginación liberada que juega con la mezcla de tomas y secuencias objetivas y no objetivas. Como resumió Man Ray en su presentación de la película en el Vieux Colombier, “lo que le doy al público es definitivamente el resultado de una forma tanto de pensar como de mirar”.

Steven Kovács –Man Ray as filmmaker. Artforum, noviembre 1972

Man Ray has written that “All the films I have made have been improvisations. I did not write scenarios. It was automatic cinema.”17 Yet the automatism of the shooting was given its final form by the montage. In the preparations for Emak Bakia he remembers that “When I felt I had accumulated enough material for a short film, I’d mount the sequences in some sort of progression, consider the job finished.”18 In the shooting Man Ray concerned himself with certain themes, movements, and effects which were combined by montage to articulate various episodes or sequences the assemblage of which created the final Surrealist film.

(…) In Emak Bakia we observe Man Ray’s first and fullest cinematic statement. His very first essay with film, Le Retour à la Raison, exhibited few of his concerns. His following film, L’Etoile de Mer, although a free rendering of a Desnos poem, is still the adaptation of someone else’s work from one medium to another. As such, it is a cinematic version of a Surrealist poem. Le Mystère du Chateau du Dés, his last completed work until the 1940s, is again too much tied to the commission from which it sprang—a movie of a party at the chateau of the Vicomte de Noailles. That these other films are also highly successful artistic efforts is to Man Ray’s credit, but in no other work does he come close to the freshness, versatility, and pure visual poetry of Emak Bakia. This is the one that stands at the junction of Dada and Surrealism. It brings together both movements on top of the underlying abstract current in a harmonious film.

(…) The comparison of two functionally different, but apparently similar objects, such as the eyes and headlights, also offers a new way of perceiving both these objects in terms of each other. In a sense, too, the rotating light forms create a new visual reality for the viewer. We find certain specific Surrealistic themes and images in the film, such as the haunting eye and the mysterious woman. The awakening process, a fundamental concern of the Surrealists who tried to abolish the barrier between the dreaming and waking states is treated. And in a wider sense, the entire film is a function of a liberated imagination playing with the intermingling of objective and nonobjective shots and sequences. As Man Ray summed up in his introduction to the movie at the Vieux Colombier, “what I offered to the public was final, the result of a way of thinking as well as of seeing.”

Steven Kovács –Man Ray as filmmaker. Artforum, noviembre 1972

Le retour à la raison (1923)

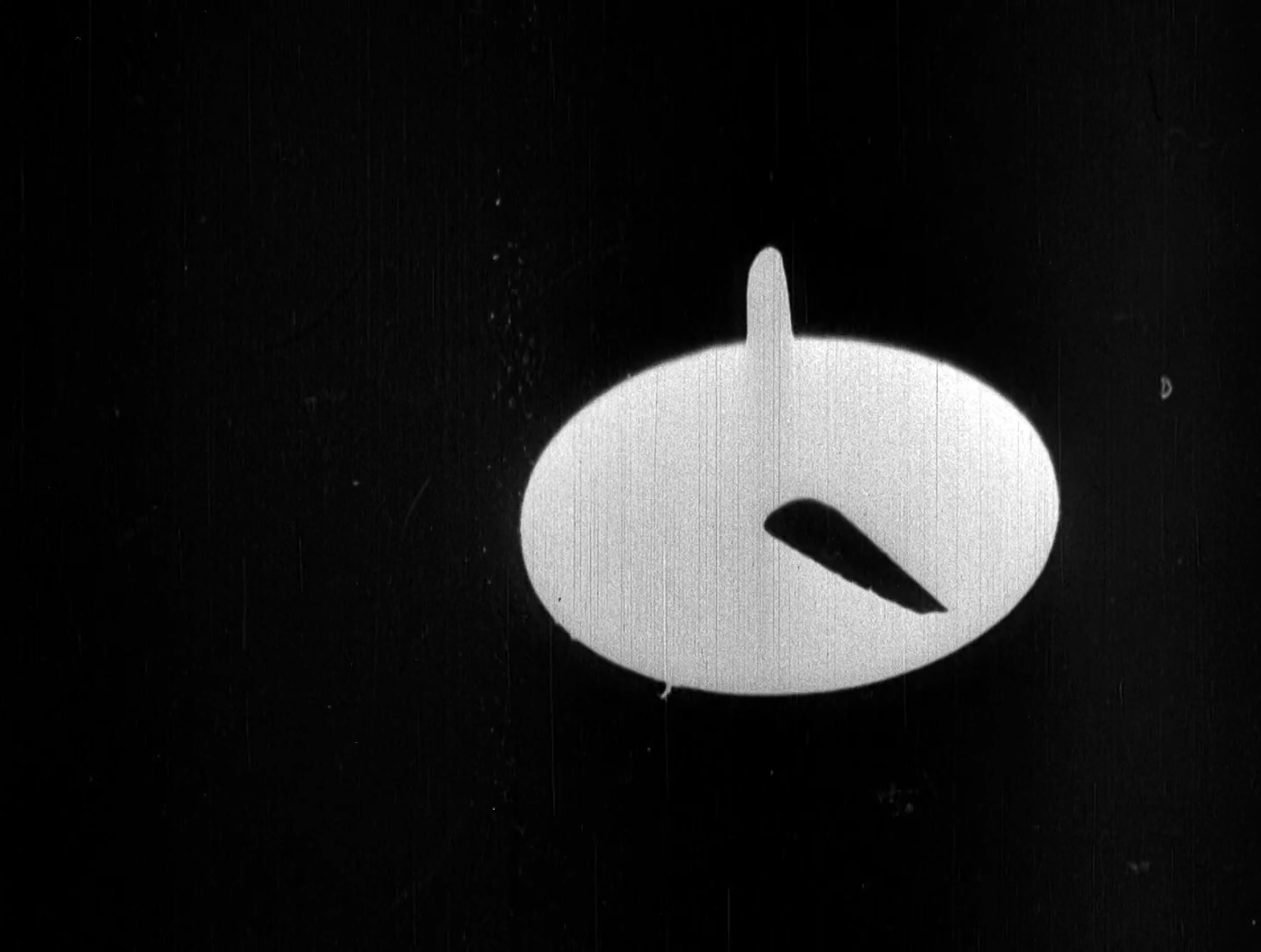

In Paris, in the 1920s, Man Ray began experimenting with photograms, pictures made by placing objects on photosensitive paper and exposing it to light. In these works, which he called “rayographs,” after himself, light is both the subject and medium. In Le Retour à la raison(Return to Reason), the artist extended the rayograph technique to moving images—he sprinkled salt and pepper onto one piece of film and pins onto another and added sequences of night shots at a fairground and a segment showing a paper mobile dancing with its own shadow. The final sequence of the film introduces Man Ray’s legendary model Alice Prin—also known as Kiki of Montparnasse—naked, her body illuminated in stripes of light.

Emak-Bakia (1927)

Emak-Bakia (Basque for Leave me alone) is a 1926 film directed by Man Ray. Subtitled as a cinépoéme, it features many techniques Man Ray used in his still photography (for which he is better known), including Rayographs, double exposure, soft focusand ambiguous features.

Emak-Bakia shows elements of fluid mechanical motion in parts, rotating artifacts showing his ideas of everyday objects being extended and rendered useless. Kiki of Montparnasse (Alice Prin) is shown driving a car in a scene through a town. Towards the middle of the film Jacques Rigaut appears dressed in female clothing and make-up. Later in the film a caption appears: “La raison de cette extravagance” (the reason for this extravagance). The film then cuts to a car arriving and a passenger leaving with briefcase entering a building, opening the case revealing men’s shirt collars which he proceeds to tear in half. The collars are then used as a focus for the film, rotating through double exposures.

When the film was first exhibited, a man in the audience stood up to complain it was giving him a headache and hurting his eyes. Another man told him to shut up, and they both started to fight. The theatre turned into a frenzy, the fighting end up out in the street, and the police were called in to stop the riot.

L’étoile de Mer (1928)

“Poème de Robert Desnos. Tel que l’a vu Man Ray”. Une femme et un homme vus au travers de vitres épaisses et déformantes. Ils montent un escalier. Elle se déshabille. Lui pas. Elle se couche. L’homme s’en va. La porte se ferme.

Des journeaux s’envolent. La femme offre une étoile de mer dans un bocal à l’homme. La chambre de l’homme. Il regarde l’étoile de mer à travers la clarté d’une lampe. Des remorqueurs quittent le port. La femme se déshabille. Elles se leve et met un pied près de l’étoile de mer.

Dans l’escalier, la femme monte un long couteau à la main. L’étoile de mer sur une marche. Le jeune homme. Une femme masquée devant lui. Elle retire son masque. C’est elle. Les murs de la Santé. La femme endormie dans son lit. La femme et l’homme arrivent par deux directions et se rencontrent. Arrive un deuxième homme. La femme part avec lui.

Le scénario de L’étoile de mer s’inspire de la lecture à haute voix d’un poème de Robert Desnos. Après un dîner avec le photographe, Desnos récite un poème de son cru, L’étoile de mer. Man Ray trouve au fil de ces phrases, matière à faire un film. Robert Desnos explique ensuite la genèse du film :

Je possède une étoile de mer (issue de quel océan?) achetée chez un brocanteur juif de la rue des Rosiers et qui est l’incarnation même d’un amour perdu, bien perdu et dont, sans elle, je n’aurais peut-être pas gardé le souvenir émouvant. C’est sous son influence que j’écrivis, sous la forme propice aux apparitions et aux fantômes d’un scénario, ce que Man Ray et moi reconnûmes comme un poème simple comme l’amour, simple comme le bonjour, simple et terrible comme l’adieu. Man Ray seul pouvait concevoir les spectres qui, surgissant du papier et de la pellicule, devaient incarner, sous les traits de mon cher André de la Rivière et de l’émouvante Kiki, l’action spontanée et tragique d’une aventure née dans la réalité et poursuivie dans le rêve. Je confiai le manuscrit à Man et partis en voyage. Au retour, le film était terminé. Grâce aux opérations ténébreuses par quoi il a constitué une alchimie des apparences, à la faveur d’inventions qui doivent moins à la science qu’à l’inspiration, Man Ray avait construit un domaine qui n’appartenait plus à moi et pas tout à fait à lui…

Qu’on n’attende pas une savante exégèse des intentions du metteur en scène. Il ne s’agit pas de cela. Il s’agit du fait précis que Man Ray, triomphant délibérément de la technique, m’offrit de moi-même et de mes rêves la plus flatteuse et la plus émouvante image”. ( Robert Desnos)

Le film est ponctué de cartons : “Qu’elle est belle”, “Après tout”, “Si les fleurs étaient en verre”….

Les musiques de Josephine Baker (C’est Lui !) ou Consuelo Moreno sont particulièrement envahissantes.

Les mystères du château de Dé (1929)

Les Mystères du château du dé fue el último de los films rodado por Man Ray como encargo particular (de los marqueses de Noailles), bajo ciertas directrices, y con posterior exhibición pública. Más allá de documentar la diversión de la aristocracia en un entorno vanguardista de lujo, es la expresión de toda una propuesta elaborada de pensamiento estético. Es un proceso de exaltación de la unión de la artes proyectado en la gran pantalla, llegando al paroxismo en la generación de un universo independiente del que nos es dado, que no es una imitación, ni un fragmento sustraído de la realidad y dependiente de ella. Man Ray ha creado un espacio para la utopía, y con ello se aproxima a toda una tradición de creadores de mundos alternativos, toda vez que culmina el proyecto regenerador que era el objetivo último del Dadá –Ana Puyol Loscertales

Les Mystères du château du dé was the last of the films directed by Man Ray as a personal request (from the marquess of Noailles), under guidelines and was subsequently shown to the public. Far beyond documenting the fun of the aristocracy in a luxury avant-garde environment, it is the expression of an elaborated purpose of aesthetic thought. It is a process of exaltation of the union of the arts projected on the big screen, reaching the paroxysm in the generation of an independent universe from the one that is given, being neither an imitation nor a fragment taken from reality and dependent of it. Man Ray has created a place for utopia, and so doing he is closer to creators of alternative worlds, and also he culminates the regeneration project that was Dada’s main aim.